// 1 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

At bedtime, it was wet with congestion, but not alarming. His first cold of the school year, an ordinary night in September. The parents in his class have been careful, keeping their kids home and taking time off when they can.

There is a grace period of a few seconds—during which I look out Henry’s window, see the velvet blue tone of the Herings’ TV, see the brake lights of someone cautiously driving home—and then the emergency hits me.

I tell Mary. She comes and listens to Henry. “He sounds croupy,” she says. We wake him, or we try to, while I call my parents and tell them to hurry over. They live a mile away. They will need to watch Adelaide, who is asleep in the nursery. Our geriatric dog will also require comfort.

By the time we’ve got Henry in the car, my parents have arrived. Mary sits with Henry in the backseat, trying to keep him conscious, splashing water on his face, we don’t know what to do, is splashing the water the right thing, we don’t know.

Empty streets, green lights. We are at the hospital before long, and the triage nurse sees Henry’s color and there is a wait but not an awful one and then he’s in the back room and they’re giving him oxygen while Mary props him up in her lap.

His color is improving. The nurse is doting on him, like she has nowhere else to be. The doctor smiles at us. She is soft-spoken, difficult to hear through her N95.

When they’ve left, I fold my hands and heckle Mary. “Adelaide,” I say, “now that’s a silly name. Why did we choose it? Who do we think she’ll grow up to be? Someone who carries a parasol around?”

Mary hushes me, pointing at Henry, who is out of the woods, we can already tell. Neither of us has slept much in the last five years, but we did just have a couple’s weekend in a lakeside cottage, and Mary’s eyes have a trace sparkle. Eventually she grins at me. “You’re pretty relaxed for someone in an emergency room,” she says.

It’s going on midnight. Henry is asleep, breathing with a religious calm. I go to fetch a candy bar from the hospital vending machine, and when I return, Mary tells me, “Adelaide is a beautiful name. You need to shut up.”

They discharge Henry around one o’clock in the morning. There won’t be a fee, it’s all covered by insurance. My parents are giddy when I update them. They’ve been waiting to hear. They must have told the Herings and other neighbors, too, because we start receiving texts from up and down the block despite the late hour.

Henry wakes up while getting buckled into his car seat. Mary is right beside him, but he focuses on me. I’m drinking him in through the rearview mirror. Though only five years old, he is terribly empathetic.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” he asks.

“I’m thinking,” I say, “that I’m taking off work tomorrow. We’re going to watch a movie in the morning, and we’ll have a picnic for lunch, and we’ll tell stories of our late-night hospital adventure.”

// 2 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

“I’ll go to the hospital with him,” I tell Mary. “You stay.”

“No, I’ll go,” she says. “You stay.”

Apart from being a terrible sleeper, Henry has been a healthy kid. Neither of us wants to abandon him now. Across the street, the Herings’ blue light is on. Mary calls India, and it takes scarcely a sentence for the two of them to settle on a plan. Moments later, India is in the house, she is taking Adelaide across the street to their spare room. Adelaide has spent a weekend with the Herings before and is comfortable with them. Their one-year-old, Rafi, is a fun playmate, and the older kids are helpful. I know the room where Adelaide will be sleeping. I can picture the wallpaper, the color of an untroubled lake.

Two years ago, we would have called my parents. But the upkeep on a four-bedroom was difficult, they said, and they wanted me and my sisters to breathe easy when they die, so they sold their house. Now they live in a different time zone, near the airport, in a town equidistant from their grandchildren. All their friends, my childhood neighbors, have moved away too.

At the hospital, once we’re settled and Henry looks better and I have trotted out a couple jokes to little acclaim, I text Gareth Hering. Adelaide is fine—she has cried out for mama twice, he reports, but is asleep now—so I ask if he can go check on the dog. But Gareth has already retrieved the dog.

“Isn’t Rafi allergic?” I ask.

Gareth says, “My mom got him actually. She loves dogs. She’ll watch him as long as you need. We found his kibble. All good.”

I tell Gareth the dog barks at everything—that he has an animist theology, that he hates trees, hates microwaves, hates silence.

“That’s my mom’s problem now,” says Gareth, adding a smiley face.

He is a banker, not the powerful sort of banker, just a paper pusher, and we connect over the mundanities of our lives: the tricycles toppled over in our driveways, the baseball game, that cloudbank coming in from the west.

Henry is looking chipper. I sneak him a bite of a candy bar while Mary uses the restroom. Once we are discharged and in the car, he catches my eye in the rearview mirror.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” he asks.

“I’m thinking,” I say, “that somewhere in our neighborhood, there is a very old woman cuddling up with a very old dog.”

// 3 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

This is his third cold of the school year, and it’s not even October. Every morning when I drop him off, I take note of the other kids in his class. They have watery eyes, runny noses, dry coughs. It’s like an infirmary. But if the other parents are irresponsible, we’re irresponsible too. With the first cold, we sent Henry back forty-eight hours after his fever broke. With the second, we waited twenty-four hours. All my sick days for the year got used up during the outbreak last February.

When I ring the Herings’ doorbell with Adelaide in my arms, India hesitates, debating whether to allow a new germ into their house. Behind her, the TV light flickers. I imagined she would hesitate, which is why I didn’t call beforehand, just showed up with a baby. But India is our friend and neighbor, and soon she reaches out for Adelaide’s swaddled body, saying, “Go, go take care of Henry,” in a scratchy voice, and then Mary and I are running red lights in the rain.

The emergency room is crowded, if not overflowing: parents with kids, kids with stuffed animals, kids in respiratory distress. Henry’s case is severe, though, and the triage nurse gets him oxygen. He is out of the woods within an hour, we can tell from his eyes, but they say he should stay a few hours more under observation.

I tell Gareth Hering that we are still in the hospital, and he says not to worry, he says that Adelaide is asleep, although their own daughter, the five-year-old, is vomiting. Anyway, if we aren’t back by morning, his mother will go check on our dog first thing, walk him and feed him. She loves dogs infinitely, he says, it’s not a problem.

The night inches along. “Adelaide,” I say at one point, “that’s a weird name we chose.”

Mary looks up. She’s half asleep, packed into a brittle chair at Henry’s bedside. “What do you mean?”

“Never mind.”

“There’s nothing wrong with the name Adelaide.”

It is four in the morning when Henry is discharged. Quiet streets, wet and dark. The doctor gave him a steroid, so he is wide awake as I buckle him in, almost jittery. Behind the wheel, I take a breath, trying to make my vision less clouded.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” Henry asks.

“I’m thinking,” I say, “that tomorrow is going to be unpleasant.”

// 4 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

We pack quickly, bring Adelaide to the Herings’, who accept her with some reluctance. Is Adelaide’s forehead warm too? I have the thought, but I don’t let it linger, it’s like a mirage, and Henry needs us more.

Hours later, when he is seen by a doctor and we’re watching him draw confused, hungry breaths, I text Gareth Hering. Adelaide has been restless, but she’s asleep now, he reports.

“Any chance you could check on our dog?” I ask.

“Wish I could,” he says, “but Rafi is too allergic.”

How allergic could Rafi be? I wonder. But it’s not the right time to press, they’re already doing so much for us.

“My mom loved dogs, too bad she’s gone,” says Gareth.

I remember that his mother died a few years ago, right when we moved into our house. Mary overheard India referring to it as a “death of despair,” a term I always equated with a drug overdose, though such an ending seemed unlikely for an elderly woman. When we came across her obituary, we learned that she lived downstate in a nursing home and had ten grandchildren scattered across the country. Perhaps, said Mary, it was despair after all.

“No worries about the dog,” I text Gareth. To Mary, I say, “He’s just a grumpy old beast, he’ll be fine,” which earns me a laugh. I try to nap, but am unsettled by hospital noises: creaking gurneys, mechanical beeps, whimpering in the corridor.

“He’s barking a lot,” Gareth texts.

Later, in the dead of night, we will return home to find our dog comatose on the kitchen floor, having clawed his way into a cabinet and consumed a dishwasher pod. This will be the sight that greets Henry after his hospital stay. And then we will have to comfort him, while I find a twenty-four hour vet, while Mary goes to retrieve Adelaide from the Herings, who are all fast asleep. Mary will finish what’s left of the night in our bed with both kids beside her, texting me sad faces and escapist travel links, while I am propped up against the wall of a strip mall animal hospital. The dog will survive the night, but we’ll put him down later that week.

For now, I nibble at a candy bar, count Henry’s breaths, hum doo-wop songs to him.

After he’s discharged, we get into the car. He touches my arm as I buckle him in.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” Henry asks.

“I’m thinking how amazing our neighbors are,” I say.

// 5 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

We need to get to the hospital right away. Mary says that I should drive, that she wants to be next to Henry, which means Adelaide needs to come in the car too. A few months earlier, we would have asked the Herings to look after her, but they sold their house when Gareth got laid off from the bank. The family that moved in after them is taciturn, prone to scowling. We used to know all our neighbors. Where have they gone?

I put Adelaide in her seat, while Mary puts Henry into his, and then she squeezes between them in the back so she can track his respiratory rate. “Drive faster,” she says, her tone urgent but controlled. Her seatbelt isn’t on, and I hear her body knocking around whenever I turn.

At the hospital, Mary gets out and carries Henry inside. Taking Adelaide in isn’t wise, there will be too much waiting, and we have to consider her health. So after a few laps around the parking lot—a moment out of time, hearing the tires swish against the wet road, hardly anywhere, hardly anybody—I drive home, console the dog, and wait to hear from Mary.

“Trying to get him seen,” she texts after a long while.

“How is he?”

“Worse.”

I fidget in the rocking chair by Adelaide’s crib. Even though Mary is doing the hard work tonight, I feel abandoned. Is that fair? I want to be in her place, by Henry’s side. I try to picture what they’re experiencing, but all that comes to mind are images from TV shows.

“Yelled at triage nurse and got him oxygen. Still haven’t seen a doctor,” Mary texts later.

An hour passes. “Nobody is masked,” she says.

“That’s scary.”

“I can’t believe the government changed the policy.”

“You can’t control that.”

“Okay.” A few minutes later: “What other viruses is he picking up right now?”

“Stop,” I say. “Is Henry okay?”

“A little better.”

I pace the hallway and look out at the neighbors’ house. Though it’s after three in the morning, the blue light of the TV is still on. It seems to fill up the entire downstairs.

The neighbors are named Avra and Louis. They have a kid, or maybe two, maybe they’re twins. I don’t know their last names.

At five in the morning, Mary texts, “Getting discharged. The bill’s going to be bad.”

Adelaide and I get in the car. I put some doo wop on the stereo and sing to her, but she cries, so I turn it off. At the hospital, Mary looks ten years older than when I last saw her. Henry has a blank face. He spots me looking at him in the rearview mirror.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” Henry asks.

“I’m thinking,” I say, “honestly, I don’t even know what I’m thinking.”

// 6 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

I try to tell Mary, but it’s difficult to rouse her. She’s been asleep for most of the day. Her symptoms align with ME/CFS, chronic fatigue, and other post-viral syndromes that we have familiarized ourselves with. Yet Mary hasn’t had any viruses in the last year. All the clinics that could treat her have endless waiting lists, and there’s no funding for these conditions, so she and I scour journal articles and message boards after the kids fall asleep.

“Honey.” I shake her lightly. “Henry has to go to the hospital.” She can’t hear me. “Hey, Mary? Mary?” In this state, she won’t be able to care for Adelaide, who still wakes up every few hours, just like Henry did when he was a baby.

If there were more time, I would make a better decision. Instead, I put Henry in his car seat and Adelaide on my lap, then back up across the street into the neighbors’ driveway. I ring their bell, with Adelaide in my arms and a small go-bag we keep ready.

Louis, if that’s his name, opens the door. The pervasive blue light, which I assumed came from a TV, issues from a giant aquarium. A dozen fish dart by. Their living room is not at all like how the Herings’ was.

“I’m sorry, my son is in the car, he may be dying,” I say, “I have to go to the emergency room, I need you to watch Adelaide, I’m sorry.” Even as Louis takes a step back, I am throwing my child at him, dropping the go-bag at his feet, and sprinting down his driveway.

Henry sounds like he’s gotten worse. I speed along Elizabeth Street. Hopefully Mary can fend for herself tonight. We have corralled some supplies—medicine, food, water—and put them in her nightstand. The dog won’t bother her. He was attacked by a roving husky on a recent walk and has been acting subdued ever since.

At the hospital, I overcome my timid nature in order to get Henry seen. It’s rare that I interact with people except through a laptop, so I forget what’s permissible, and I go overboard, I weep like it’s a Greek tragedy. “My son! My son is dying!” It’s a performance, it feels ridiculous, but it’s true on some level, and soon, a nurse brings oxygen to the waiting room. They hook it up to Henry. His breathing relaxes.

I text Mary an update. She reads it but doesn’t reply.

When I decide to check on Adelaide, I realize I don’t have Louis’s number. I try to find contact information on the neighborhood email list, but searches for “Louis” and “Avra” don’t turn up anything. Most of the messages on the list are about stray dogs, missing packages, illegal fireworks, gunshots.

Henry’s respiratory rate has fallen below 30, and his oxygen saturation is at 97. He is acting chipper, listing every animal that hibernates, he may be out of the woods, who knows. I send all these updates to Mary, but she doesn’t read them.

Is Adelaide safe? I consider sending an email to the whole neighborhood, but what would I say? That I left my daughter with someone I barely know?

Everybody is trying to fall asleep in the ultra-bright waiting room. My head hurts. Am I feeling lonely? Am I angry? Lately I’ve been listening to a podcast about mental health. The host says not to blame the people in your life, not to blame politicians, either. She talks about taking 100% responsibility for your life. “In the end, only you are responsible.” Even if I disagree, her voice is soothing.

The hands of the hospital clock puzzle me. Is it 4:15? Or 3:20? Why is the second hand galloping by? Eventually Henry is seen by a doctor. In the middle of the examination, I ask her what she knows about chronic fatigue. Are there any clinics nearby? “I don’t know about that,” she says curtly. So I interrogate the nurse. But the nurse has just emigrated from Poland, there is a nursing shortage here, he doesn’t know any clinics, he’s still figuring out the basics of everyday life, where to do his laundry, what his debit card PIN is.

“Are you getting these texts?” I say to Mary.

This time, she writes back. “Adelaide is home. I can’t believe you did that.”

They give Henry another round of oxygen, while I bite my bottom lip to fight off a panic attack. Where are my parents?

It is nearly six when Henry is discharged. Not much will be covered by insurance, they tell me at the desk. Buckling him in, I scour my banking app. He watches me with hangdog eyes.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” Henry asks.

“I’m thinking,” I say, “that we should drive around for a while before we go home.”

// 7 //

When I go to check on Henry, his breathing is desperate.

I wake Mary, but she is too fatigued to move, so I scoop her up and carry her like a bride to the double bed in Adelaide’s nursery. I set her up with milk and diapers. Then I grab Henry.

All night there have been fireworks on our street. Or possibly gunshots. This ambiguity arose in the nights leading up to July 4th, when people began setting off fireworks in their driveways. But there was also a hold-up at a convenience store on Elizabeth Street and a shooting several blocks away on Primitive Street. It was never clear which sound we were hearing. On the neighborhood email list, people turned it into a game: Fireworks or Gunshots?

Henry is in my arms, limp, but as we exit the house, he makes a gasping noise and points down at my feet. There is a bullet on our porch. Shiny, pristine, never fired. It’s as if someone placed it there deliberately. Who can I ask about it? The house across the street is empty. When the Herings moved out, nobody moved in. All the other houses have their shutters closed.

The bullet feels like a warning, or at least a sign, and I find myself driving an extra ten miles to a hospital in the suburbs, where I know we’ll be safe. But Henry’s breathing is so loud, and as I take the off-ramp, I fear I made the wrong decision, I shouldn’t have driven all the way out here, because even in the suburbs there are flu-ish kids with stuffed animals clogging up the waiting room. The other parents seem to know the doctors, they get called in fast, and meanwhile I’m asking to borrow an inhaler from whoever remains behind, even though Henry’s medication is slightly different, I forgot the go-bag with his inhaler, but a random inhaler can’t hurt, can it? And I’m giving him water from the dirty fountain in the hallway, cupping the water in my bare hands, his water bottle is in the go-bag too, how could I forget it, I was so tired and so frightened of the gunshots (or were they fireworks?), I didn’t bring anything except my keys and my wallet and the stuffed animal that Henry was clutching while he tried to breathe.

“Adelaide cried. I put her in the bed with me,” Mary texts. “The dog barfed.”

“Where?”

“Not sure, I just heard him. It woke Adelaide up.”

“That’s a weird name we chose. Adelaide.”

“Okay.” A minute later. “Henry’s hanging in there?”

“Waiting to be seen,” I say.

“Is he okay?”

“Not great. They say he’s triaged, they say he’s not in imminent danger.”

Mary and I text each other in this rapid-fire manner, yet soon she is worn out, and I am left cradling Henry, uncertain whether his lungs will shut down. We would share our pain with other people if we could. There’s nobody else, though, just the four of us, our isolated family. Mary and I haven’t had a night away in years.

It’s five in the morning when they call Henry’s name. The hospital is manically bright. A doctor gives him some oxygen and an oral steroid, and says it’s good I didn’t want any longer to bring him in. While Henry takes deep breaths, I prop myself up against the wall and wonder how many nights like this we are capable of.

We are discharged as the sun is rising. I buckle Henry into his car seat, my vision foggy. He puts his hand on my arm.

“What are you thinking, Dad?” Henry asks.

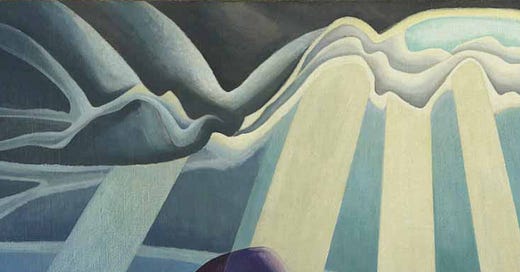

“I’m thinking,” I say, “about Lake Baikal in Asia. The oldest, deepest lake in the world.”

“When did you go to Asia?”

“Never. I’ve just seen photos.”

“Let’s go home,” he says.

It rained more overnight. The roads are slick. We leave the suburbs, enter the city, and pull into our driveway.

“Where are we?” Henry says.

“Home.”

“No, we’re not.”

And he’s right. This is my parents’ house, the one they sold two years ago. It’s also the house where I grew up, the house where we ordered pizza every Friday night, the house where our neighbors gathered to watch the World Series, where people were always gathering, in fact, like it was a village green. It’s the house where I was a baby, timid but carefree, a lifetime ago.

“I want to go home,” says Henry.

Slowly, reluctantly, I drive away.

This story originally appeared in Pithead Chapel.

We are so back